Trap-neuter-return on a state scale

Government agency and humane groups join forces for Delaware’s community cats

Given the often inflated concerns batted about in the media about public health threats from community cats, the fact that there is a managed community cat colony on the New Castle campus of the Delaware Department of Health and Social Services may be surprising. Not only is the agency supportive of trap-neuter-return (TNR) as a tool to reduce the state’s free-roaming cat population and limit disease transmission, it is also home to the state’s Office of Animal Welfare.

OAW was established in 2013 to consolidate and coordinate companion animal programs statewide. The agency is responsible for the state’s low-cost spay/neuter program, animal shelter standards, dog licenses and emergency response for animals as well as centralizing animal control and cruelty enforcement. And according to its executive director, Hetti Brown, “The animal welfare issue in our community that requires the most attention is the community cat issue.”

Delaware is one of a number of states that don’t require (or fund) animal control agencies to pick up cats running at large. With mounting public pressure to end the euthanasia of healthy cats, most Delaware shelters ended open-admission policies for cats in 2010, managing intake for owner-surrendered cats and only accepting friendly strays when space was available. While this significantly increased live-release rates—to a statewide average of 95 percent for felines—the question remained for Brown: “How do we ensure cats not accepted into adoption programs and shelters still remain healthy and are not reproducing to exacerbate the stray cat population?”

The answer was to expand TNR efforts in the state through a collaboration that includes OAW; Forgotten Cats, a nonprofit that operates Delaware’s only high-volume statewide TNR program; and the Brandywine Valley SPCA (BVSPCA) in New Castle, OAW’s shelter partner.

OAW provides small grants for TNR, training for volunteers and free surgeries during the annual State Spay Day. State humane officers are in the field every day explaining the benefits of TNR and helping resolve conflicts with humane deterrents and sage advice. With support from OAW, Forgotten Cats received a $200,000 PetSmart Charities grant last year for 4,000 targeted community cat surgeries.

In April, the BVSPCA launched the first statewide return-to-field (RTF) program. Since humane officers don’t pick up stray cats, the program is a little different from other RTF (also known as shelter-neuter-return) programs, but it provides a similar service to the community. Concerns about community cats—which are the majority of calls OAW receives—are redirected to the shelter’s community cat coordinator, who provides humane traps and other resources for TNR. By encouraging caretakers and other concerned residents to participate, BVSPCA staff can spend their time trapping large colonies that are beyond the scope of most individuals.

Adam Lamb, CEO of the BVSPCA, likens the public’s response to the opening of floodgates. “There is a lot of excitement about it because there has been a lack of service for quite some time,” he explains.

Right now, the statewide RTF is a pilot project, with funding secured for six months. One of the program’s goals is to show the need for service—with agencies not having data on stray cat intakes, it’s hard to determine the extent of the problem. As the program gains footing, the BVSPCA will look to how it can further complement the efforts of OAW and Forgotten Cats.

Effective TNR can be challenging when your territory covers an entire state, but Forgotten Cats employs a methodology that has resulted in a zero-growth rate for the colonies it tackles. Mass trapping is their key to success, and they don’t leave a site until all the cats have been sterilized. This means trapping 24 hours a day and holding all the cats until the last one has been trapped, which usually takes about five days. It is a commitment that relies on residents to monitor the traps and volunteers to help transport the cats to and from clinics and to care for them while they await return home.

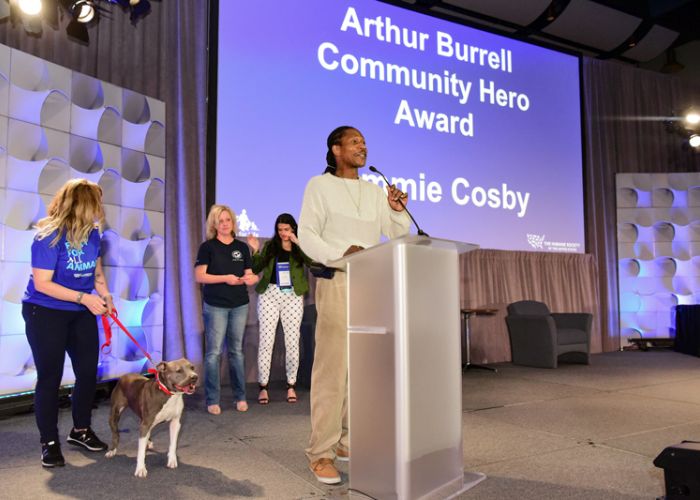

At any given time, there may be 200 traps set and 20 different colonies trapped in a week, which translates to 10,000 cats spayed and neutered each year. With just a small staff of two trappers and a network of 450 volunteers, Forgotten Cats tries to make it as easy as possible for people to participate. “Because of that, TNR has gotten a pretty good name in Delaware,” says president Felicia Cross.

To help keep it that way, OAW also organized the Free-Roaming Cat Coalition, which brings wildlife advocates and veterinary groups into the fold, recognizing the common goal: to minimize the community cat population for the benefit of cats, wildlife and public health.

“Always stick to the common goal,” advises Brown. That principle is driving a successful statewide effort for community cats.