Ask the Expert: Dr. A. Michelle González

Ohio veterinarian describes the value of necropsies and why veterinarians shouldn’t be afraid to perform them

After her cat returned home from an outdoor jaunt and died, the owner was certain that her neighbor was responsible.

“He poisoned my cat,” she told veterinarian A. Michelle González, who often hears similar theories from people whose pets have died unexpectedly.

In this case, the cat’s body told a different story. While performing the necropsy, González discovered the animal had been suffering from a blocked urinary tract.

“The bladder was huge,” she says, adding that the cat’s unsteady gait and “acting drunk,” which the owner attributed to poisoning, were actually caused by the toxins that accumulated in the cat’s body due to the blockage.

It wasn’t the answer the owner expected, but it was an answer. That’s what González is seeking whenever she does a necropsy, the term for an autopsy performed on an animal.

“We have to be a voice for animals whether they’re alive or deceased.”

—Dr. A. Michelle González

Most days, González is focused on saving animals’ lives through Rascal Unit, the mobile veterinary clinic she founded in 2006 to bring affordable spay/neuter and wellness care to Ohio communities where such services are scarce. In her spare time, she works to determine the cause of death for animals who can’t be saved but whose bodies can provide vital information for grieving owners, shelters concerned about a potential disease outbreak, and local and national humane organizations dealing with suspected cruelty cases.

Necropsies are a valuable but underused tool in veterinary medicine, González says, partly because many veterinarians lack confidence in their ability to perform them and partly because many pet owners don’t know they’re an option. In late 2022, she launched the Animal Welfare Junction podcast to bring more attention to veterinary forensics, which includes performing necropsies, processing animal crime scenes, handling and interpreting forensic evidence, and more.

“We have to do better,” she says. “We have to be a voice for animals whether they’re alive or deceased.”

In this edited interview, González describes what veterinarians, animal advocates and pet owners should know about necropsies.

What led to your interest in veterinary forensics?

I’ve always been interested in forensics and criminology in general. I completed a master’s degree program in veterinary forensics at the University of Florida. That taught me things they don’t teach you in vet school, but it also created a lot of questions, such as “Why do people do this?” So I did an online master’s program in forensics psychology and then completed a master’s in forensic science, which showed me some of the things that are done in human cases that could potentially be done in animal cases. I’m now pursuing a master’s degree in animal law through the Lewis & Clark Law School, because it’s so important when you’re working with criminal cases to know what the rules are. I’m an eternal student.

When should a necropsy be performed?

I think a necropsy should be performed any time a cause of death isn’t known, but especially if you’re concerned it’s an infectious disease or there’s a concern about neglect or cruelty. But even if you’re doing a routine surgery and an animal dies under anesthesia, instead of just assuming it was a reaction to the anesthesia, you can get so much information from doing a necropsy. You may find out that there was a diaphragmatic hernia or some other condition. It gives you information you can use in the future and closure for the caretaker.

Is it common for people to have a mistaken belief about what caused their pet’s death?

A common scenario I see is where an animal allowed outside has died unexpectedly, and the first thing out of the owner’s mouth is, “My neighbor did this.” But it’s not always poisoning, and not every poisoning is intentional. As a general practitioner, I’ve seen animals who have died and done a general necropsy and found the blue-green changes in the stomach that are consistent with rat poison. Rat poison is made to be tasty for rats, so it’s going to be tasty for dogs and cats. Sometimes, unfortunately, dogs and cats get into things that they shouldn't.

A different type of case I handled involved an owner who had taken her 8-week-old puppy to the vet to be vaccinated. The next day, she left the puppy at her friend’s house while she was at work. Later in the day, her friend called and said the puppy died and is bleeding where they gave the vaccinations. The friend told her the puppy died because the vet gave the vaccinations too forcefully.

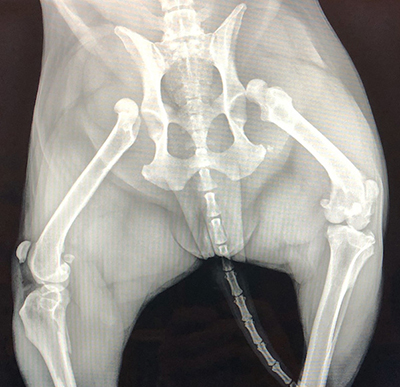

When I examined the body, there was a significant amount of blood from the left side of the puppy. Since most vaccines are given on the right side, that was the first hint that the story might be wrong. We did X-rays and shaved the puppy and found a lot of bruising, puncture wounds, trauma to muscles and broken ribs. The findings were consistent with a crushing injury also with penetrating wounds, and the most likely scenario was a larger dog had done this. After I discussed the findings with the owner, she called her friend, who admitted that her adult dog had killed the puppy. The friend just hadn’t wanted to tell her the truth.

It sounds like necropsies can also benefit veterinarians whose clients might otherwise blame them for a pet’s death?

That’s true. In one of my cases, a dog was hit by a car, and the owner took him to an emergency vet. The owner wasn’t happy with the information the vet gave him, so he decided to take his dog to another emergency vet facility. The dog died in transit. The owner wanted a necropsy because he thought the first vet missed something. I found that the dog had multiple tears of the lungs and what’s called tension pneumothorax. It wasn’t that the veterinarian missed something; the dog just unfortunately had a severe life-threatening condition.

The owner wanted to find fault with this vet and paid me for a necropsy that didn’t find fault with the vet. As a forensic veterinarian, you need to be as objective as possible. You’re being hired by a person or group, but that doesn’t mean you’re going to create a narrative to fit what that person thinks.

Are there limits to what a necropsy can reveal?

It depends on the type of problem that resulted in death and the time since death. The longer a body decomposes, the harder it is to get information. If you find an animal who may have just been killed but put the body in a room at room temperature for three days, there are going to be changes that affect your findings. So you want to freeze the body if you’re not able to do an exam quickly.

When you’re doing a necropsy, traumatic injuries are typically easier to find than disease processes, although you don’t always know what caused them. But you can tell whether it’s sharp—such as an injury caused by a knife or screwdriver that leaves sharper edges—or blunt trauma, when tends to be more superficial unless it’s severe blunt trauma from being hit by a car. You can also find things that might indicate prior abuse, such as old fractures of the ribs and hips.

For some things, you need to collect samples to get more information. So if there’s a possibility of poison, you can collect liver and kidney samples and stomach contents for analysis. If you have a dog you think might have died of parvo, you can collect intestinal samples and send them out. Some of the most common tests I send out on necropsies are bone marrow fat analysis, which I send to the toxicology department at the university to evaluate for malnutrition, and liver samples for toxicology analysis.

Sometimes you can’t find any problems, such as if it was a reaction to the anesthetic during surgery or an unknown heart rhythm disturbance or neurological condition. You can’t detect those issues when they’re dead. But a necropsy is always going to give you some information. Even if you couldn’t find anything, that tells you something. You know, for example, that this wasn’t a foreign body or obstruction, a gunshot, fracture or trauma. You may not know exactly what happened, but you can say this is not what happened.

Can any veterinarian perform a necropsy, or do you need special training?

Most vets should be able to perform a general necropsy. A necropsy can be seen as a surgery, similar to an exploratory on a live animal.

The issue with a forensic necropsy is that now we’re talking about a potential legal case, and everything has to be documented properly. Many vets can do it; I don’t want to scare veterinarians into thinking, “I don’t want to touch this, because I’m gonna get in trouble if I do it wrong.” But you need to document everything very, very well. You need to communicate with investigators or humane officers about what information they need and what information they have, such as where the body was found and how it was found. You don’t want to go in blindly.

There are a lot of resources out there. Shelter Medicine for Veterinarians and Staff, Investigating Animal Abuse Crime Scenes and Veterinary Forensics—those three books together can help you build a protocol so you’re not scrambling every time you have a case.

If you’re scared—well, do it scared. And if you make a mistake, document it. The worst thing you can do is be a witness to animal cruelty and not doing anything about it.