Social justice and animal welfare

How Pets for Life and Rural Area Veterinary Services have helped bring issues of equity and access to care into the animal welfare conversation

In one sense, it was a routine grooming appointment. In November, a big poodle mix named Freeda got her curly black hair shampooed, cut and blow-dried to perfection. She went in looking good and came out looking better, ready to show off her new ‘do to mom Janis at their Northern Idaho home. (Janis prefers to be identified by her first name only.)

In another sense, it was a momentous event. A few days later, a van rolled up to Janis’ home and Kendra Dodge from the Better Together Animal Alliance stepped out, hands full of balloons. The snow crunched underfoot as Dodge and Janis offered squeaky toys to Freeda, showering her with praise.

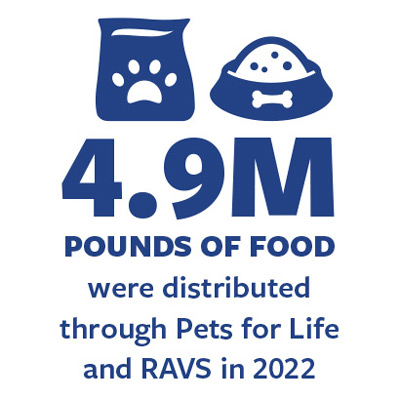

It was just another day for Freeda, who’s accustomed to being the center of attention. But for the Better Together Animal Alliance and the Humane Society of the United States, it represented a milestone: Freeda’s grooming was the 1 millionth service provided under the Pets for Life umbrella.

Providing what pets and people need

It might seem like a small thing, giving a dog a bath and a haircut. But grooming keeps dogs like Freeda from getting painful, matted hair. Amanda Arrington, HSUS vice president of access to care, says she’s seen too many instances where an ungroomed dog led to citations or criminal charges for “lack of care.” Yet the service can be pricey, and groomers often require proof of vaccination, a struggle for people who can’t access veterinary care.

When you multiply that one grooming service times a million, you get a million small acts that add up to something big: a radical reframing of the way we care for pets and their families. The HSUS Pets for Life program has helped lead that reframing as it makes pet care more attainable.

Today, some 20 million pets live in poverty with their families across the U.S.—and 70% of those pets have never seen a veterinarian. It’s not for lack of interest or desire; 28% of all pet owners report an inability to access veterinary care.

Since 2011, Pets for Life has been working to bridge that gap between pet care and the animals who need it. The program provides resources such as veterinary care, spay/neuter services, grooming, behavioral training, supplies and more at no cost to people and their pets in underserved communities. Teams operate out of two flagship locations in Los Angeles and Philadelphia, but even more work happens at 50-plus mentorship partners across the country—including the Better Together Animal Alliance in Ponderay, Idaho, where Janis is a client.

Building on the Pets for Life philosophy, mentorship partners such as the Alliance work within their communities to build trusting relationships with clients and connect them with resources. The bedrock of that philosophy? That love for animals crosses all boundaries, says Arrington. “That regardless of someone’s income, regardless of someone’s background or what zip code they live in, that animals are an important part of people’s lives.” And the corollary? People deserve to stay with their pets—and pets with their people.

The same principle has informed the HSUS Rural Area Veterinary Services program since 2002. With a focus on Native communities, RAVS brings veterinary care to tribal lands with significant rates of poverty and unemployment—particularly rural ones. “They might be 50 or 100 miles away from the nearest veterinary practice,” says Windi Wojdak, senior director of RAVS. “So even if economic issues were on balance, the geography then adds another layer of transportation barriers.”

What sets RAVS apart is that it includes a veterinary teaching component. Each MASH-style spay/neuter clinic is staffed by volunteer veterinarians, veterinary technicians and vet students. The goal for students is twofold: to provide hands-on training opportunities and to provide experience with access-to-care issues.

It’s one thing to read statistics about poverty and under-resourced communities, says Wojdak. It’s another to see firsthand the barriers people can face to accessing pet care. “I don’t know how many times I have had students have true-life lightbulb moments,” she says. “That direct experience is absolutely life-altering.” Students often come away newly inspired to volunteer or work with under-resourced communities.

Helping pets, helping people

When we offer access to pet resources, says Arrington, “it’s not just an animal service, it is a human service.” The bonds between people and animals go deep, with proven benefits for human health: reducing cortisol (a stress hormone), lowering blood pressure, reducing feelings of loneliness and so much more—as anyone who has loved an animal knows. Ensuring people can maintain those bonds by keeping them with their pets is a profound service.

But the issues Pets for Life and RAVS address don’t occur in a vacuum. Access to veterinary care, access to pet resources, a lack of pet-inclusive housing, “all of that is connected to larger systems of inequity that people experience,” says Arrington. “And because pets are part of families, it’s going to impact animals as well.” If a family struggles to purchase cat litter because they don’t have a car and public transportation is scarce, they’re not only struggling to care for their cat—they’re likely struggling with broader transportation and access issues.

It’s easy to oversimplify the problem, to suggest that “if we just have enough spay/neuter programs, the world will be OK,” says Wojdak. But asking why some communities don’t have veterinary clinics and why some communities have lower rates of altered pets can lead to some hard truths. Maybe those communities have historically been subject to racist redlining policies, leading to fewer investments in housing and resources. Maybe those communities have been left out of the animal welfare conversation, and they’re making the best decisions they can with the information (and resources) they have.

That nuance can get lost in discussions about equity and access to care, especially within the animal welfare community, where emotions often run high. All too often, we forget that not everyone has the same background when it comes to animal care.

“There’s this assumption that everybody is operating from the same sheet of music,” says Tai Conley, HSUS senior principal strategist of diversity, equity and inclusion programs. It comes from a good place; we all love animals and want to see them thrive. But what if we’re not on the same page? What if pet care looks different in one community from how it looks in another, and what if providing services and support ensures that a family can enjoy the love and companionship of an animal in the way that makes sense for them?

Animal welfare organizations’ actions tend to reflect a specific set of beliefs: that all pets must be adopted, immediately sterilized and cared for in a very specific way using very specific products and approaches. That attitude is often echoed on social media and elsewhere: If you can’t afford a pet, you shouldn’t have one. Programs such as Pets for Life and RAVS challenge that assumption, asking us to broaden our understanding. Is it better to remove a pet from a home because her guardian can’t afford kibble at the end of the month, when money is extra tight? Or is it actually better—for animal and human alike—to connect her guardian with a pet food pantry, preserving their bond?

Taken to its logical conclusion, the argument about affordability suggests that only people with a certain socioeconomic status and certain living arrangements are worthy of having a pet, says Conley. And that “really flies in the face of what we’re looking to do when we’re talking about homing pets. It only exacerbates a problem versus creating solutions.”

“Are we saying that euthanization is a better option than a loving home that just doesn’t have as much financial resource?” asks Conley. “Are we saying that these animals would rather be in unfamiliar environments like a shelter than with the families they’re familiar with?” And if the answer is no, then what does it take to keep pets with the families who love them—and to offer the resources those families need?

Meeting people where they are

When we talk about increasing access to care, affordability tends to dominate the conversation. Yet affordability is only part of the story.

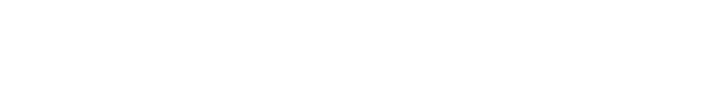

“The first thing that folks tend to think is that it’s all about economics, right? And that if it’s just affordable, if it’s free care, then it’s accessible,” says Wojdak. In reality, “access” is more complex. Building on principles used in human social services, the HSUS defines “access” as providing resources that are available, attainable, affordable, appropriate and accepted.

The nuance is critical, and it reflects the approaches taken by Pets for Life and RAVS for decades. “Equity is about meeting people where they are to produce equal outcomes,” says Conley. It’s tailoring the approach to the community and going in without judgment or preconceptions. It’s why the HSUS fights for access on multiple fronts, with policy professionals advocating for pet-inclusive affordable housing and supporting the expansion of veterinary telemedicine.

We all come to the proverbial table with different backgrounds, levels of awareness, resources and even willingness to engage with the animal welfare movement, says Conley. “Equity is the act of getting more people involved. If we think about it, it’s the conscious practice of making this [movement] more accessible,” she says.

Conversations about economic, racial and social justice can be tough. Solutions are multifaceted, requiring creative, systems-level thinking. But that shouldn’t scare us off—and we shouldn’t believe that caring about these issues will detract from our work for animals, says Arrington.

In fact, “it is mission critical for us to do so,” she says. Giving people a solid foundation and emotional space to care for their pets is a powerful way to help animals and keep them in loving homes.

The future of pet equity

This year, the HSUS is expanding the conversation about pet equity with the More Than a Pet campaign, which launched in May. To honor the love people have for their four-legged family members, the campaign highlights how the bond transcends race, ethnicity, geography and socioeconomic status, and how an animal is indeed more than a pet. Its goal is to ensure pet-owner support programs such as Pets for Life and RAVS can continue doing what they’ve always done: celebrating the human-animal bond and nourishing it by ensuring people have what they need to care for their pets.

Both Wojdak and Arrington are hopeful about where this conversation can take us, not just as animal welfare advocates, but as people who care about other humans, too.

Arrington acknowledges that it’s easy to get impatient. “When you’re in the middle of it, it can seem slow,” she says, but stepping back offers perspective.

There’s been progress in the tenor of the conversation around these issues. Just a decade ago, says Arrington, almost everyone bought into the belief that if you can’t afford a pet, you shouldn’t have one. Pets for Life, with its nonjudgmental approach of simply meeting people where they are, was quietly radical.

“There wasn’t just a disagreement on the philosophy that Pets for Life was promoting. There was real pushback,” says Arrington. Naysayers suggested that Pets for Life would “enable” people who “shouldn’t” have pets, or that community outreach wasn’t safe, or that underserved communities were rampant with animal cruelty and fighting. These days, as conversations about equity have become louder, the naysayers have gotten quieter.

Change has been “so incremental that it’s easy to not see the progress,” adds Wojdak. But when she reflects on her 20 years doing this work, Wojdak does see it. Then, students joined RAVS primarily for the hands-on clinical experience. As for topics such as shelter medicine and access to care, “none of that was part of the conversation at all,” she says. Today, students learn about these issues in school.

Wojdak also sees progress in the types of issues RAVS addresses. These days she notices fewer preventable illnesses, such as canine parvovirus and sarcoptic mange, and she says more animals are receiving vaccinations and preventive care.

The change is worth celebrating. “When you look at how long animal shelters have been around and how long the humane movement has existed, for this part of the work to catch on as quickly as it has, I think it’s something that all of us collectively should give ourselves some credit for,” says Arrington. “It’s a very significant shift happening. And I see it really just becoming foundational to our identity.”

If the fight for pet equity sounds big, it is. If it sounds hard, it is. But, says Arrington, we’re already doing the work. Now we have to name it and expand it.

Meaningful change won’t happen overnight. “What does this look like 20 years from now? These aren’t three-year goals right? This is the course of my entire career,” says Wojdak.

Real change requires groundwork, and organizing, and advocacy. It requires reaching hearts and minds. It’s what we’ve been doing, and what we will continue to do—all of us together, creating a more equitable world for people and their pets.