Closing the door on the gas chamber

Efforts to eliminate gas chambers nationwide have been largely successful, but the fight isn’t over

There weren’t any gas chambers in California animal shelters; a 1998 state law banned them for the euthanasia of cats and dogs. At least, that’s what the animal welfare community thought.

That’s why Brandy Kuentzel, general counsel for the San Francisco SPCA (SFSPCA), was surprised one day in the fall of 2015 when a colleague forwarded her a “whistleblower-type” email, she says, from someone in California’s Central Valley region. She says the basic message was: “Hey, animals are being gassed out here where we live—is this legal?”

Kuentzel wasn’t alone in assuming it was illegal. She reached out to The HSUS and the UC Davis veterinary school for assistance, and they also thought chambers in the state were “a thing of the past,” she says.

In fact, gas chambers in the whole country are almost a thing of the past, thanks to efforts by national and local animal organizations, including The HSUS, which have worked to get rid of them for the euthanasia of dogs and cats because they don’t provide a humane death.

It turns out there was a loophole in the California law that made the carbon dioxide chamber legal in the city shelter in small, remote Coalinga. The law banned only carbon monoxide chambers, inadvertently leaving out carbon dioxide, another commonly used gas.

Later, Kuentzel and the SFSPCA staff would find out the chamber was homemade; it looked like a large Rubbermaid container with hoses connected to pump in the gas. That wasn’t the shelter’s only problem, either.

“The conditions that we saw there were heartbreaking,” says Kuentzel. “… They didn’t even have enough resources to pay for hand soap. … They didn’t have a single leash on the premises.”

The shelter’s estimated 600 animals (but probably more, says Kuentzel) who came in annually were recorded at intake on a whiteboard. Once they were put in the chamber—because with no adoption program and just a couple of rescue partners, that’s how most of them left the shelter—their names were erased, and they “ostensibly no longer ever existed,” says Kuentzel.

The SFSPCA realized the shelter was using the gas chamber as a last resort—a consequence of a slim operating budget (under $10,000 a year) and an isolated location (more than 45 miles from the closest veterinarian) that made it nearly impossible to access the drugs needed for euthanasia by injection—the most humane method—because of state laws, says Kuentzel. (Run by the Coalinga Police Department, the shelter had been trying “for years” to partner with a veterinarian so staff could euthanize animals humanely, says Lt. Darren Blevins.)

Shocked at these conditions, the SFSPCA set out to help.

Changing history

Since the birth of the U.S. humane movement in the late 1800s, shelters and animal welfare advocates have searched for kinder alternatives to the drowning, clubbing and public shooting methods that were once used to dispose of unwanted dogs and cats.

Of course, shelters have made it a priority to reduce and prevent euthanasia in the first place and have made progress—about 3.4 million cats and dogs were euthanized in 2013, compared to about 15 million in 1970.

“Everything we do with respect to euthanasia is couched in terms of: We’re working toward eliminating euthanasia of any healthy, adoptable animal entirely; we’re all working for that day,” says Inga Fricke, director of HSUS pet retention programs, who has led the organization’s charge to close the chambers. “But when it does have to be done, we’re making sure it’s done as humanely as possible.”

Like many methods of the past, including decompression chambers and electrocution machines, gas chambers were once considered a route to a humane death. In theory, they could have been, but in practice, these chambers didn’t provide a quick, painless, stress-free end of life—which is the standard for a humane death. Euthanasia by injection (EBI), using a lethal dose of a barbituate, emerged in the 1960s; today, all major animal welfare organizations, including The HSUS, National Animal Care & Control Association and Association of Shelter Veterinarians, as well as the American Veterinary Medical Association (AVMA), recognize it as the most humane form of euthanasia.

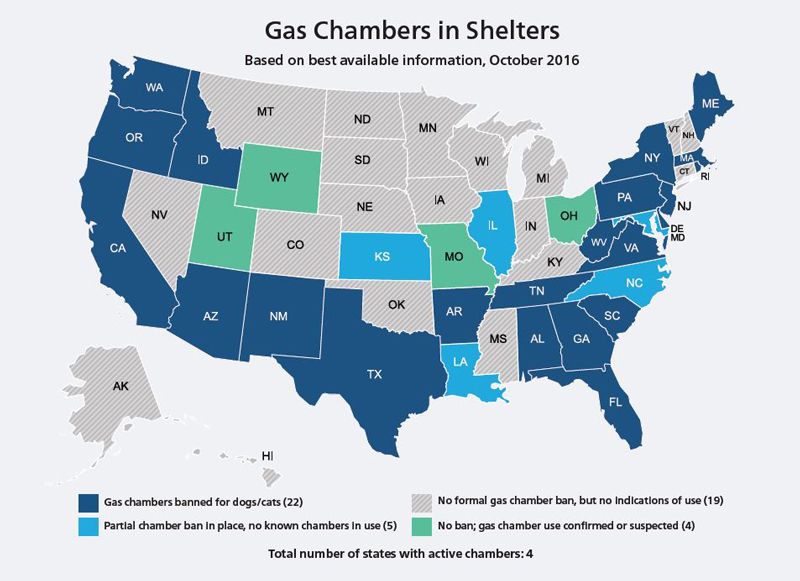

But the methods of the past can be hard to dislodge, and at the start of 2013, shelters in 16 states still had operating gas chambers.

A lot of the time, shelters just want to keep using chambers because they have a “this is how we’ve always done it” attitude. “It’s not that anybody wants to inflict pain on animals,” says Fricke. “It’s about that comfort level and familiarity and resistance to change.”

Through a combination of advocating for statewide bans and helping shelters transition to EBI, The HSUS has helped close more than 70 chambers over the past three years. Today, there are fewer than three dozen known chambers in four states.

But, as evidenced by the events in California, there can be unforeseen challenges. Some state bans have loopholes. When a state doesn’t have a ban, it’s difficult to determine if any chambers are still in operation. And often, the shelters that still use chambers have myriad other issues.

Each chamber that is closed is a win for the animals, the shelter and the community, but The HSUS’s ultimate goal is to pass a legal ban for gas chamber euthanasia of cats and dogs in every state, so once chambers are a thing of the past, they’ll stay there.

Humane euthanasia

Most of the humane community has recognized the problems with gas chambers for decades, but a recent change to the AVMA euthanasia guidelines lent fuel to their arguments. Under the new guidelines, EBI is the only acceptable method of routine euthanasia in a shelter setting. However, carbon monoxide and carbon dioxide gas chambers are still “approved with conditions” for companion animal euthanasia, changed from just “approved” in 2013. It may sound like a small distinction, but “it’s important to understand what those conditions are,” says veterinarian Michael Blackwell, HSUS chief veterinary officer and board member for the Humane Society Veterinary Medical Association, an HSUS affiliate. “In the case of gas chambers, [the AVMA stance] comes down to this: In order to properly, humanely euthanize dogs and cats and other animals that are in shelters, the gas needs to be administered at the appropriate rate and appropriate dose.”

Technically, if all of the conditions are met, the death will be pain-free—but that’s more likely in a laboratory setting, not the reality of a shelter, says Blackwell. (Experts question whether any exposure to a non-anesthetic gas like carbon dioxide can be humane, even in the highly controlled environment of a laboratory, says Fricke.)

Take the Coalinga shelter, for example. That rigged Rubbermaid container wouldn’t have complied with the AVMA’s conditions. Neither would the homemade chambers once common in North Carolina and other states.

When it comes down to it, most chambers in shelters aren’t built or used in a way that complies with the AVMA’s conditions. Even in the unlikely event that the gases can produce a painless death, it’s stressful for an animal to be locked in a dark, unfamiliar box, with the smell of death inside, says Blackwell. They often die clawing at the inside of the chamber, desperately trying to get free.

Euthanasia expert Doug Fakkema became an advocate for EBI in the 1970s after doing it for the first time and realizing “it was such a profound change” from other methods, he says.

With EBI, animals slip from consciousness to death through the use of approved euthanasia drugs; they experience no pain and are held by caring, compassionate people. If anything is telling, it’s that EBI is the method that private-practice veterinarians use to euthanize their clients’ pets.

Overcoming barriers to change

Recognizing the significance of the change to the AVMA guidelines, some state veterinary medical associations decided chambers were not an acceptable form of euthanasia. But since they’re not completely banned, some states continue to use them.

Some say it is because EBI is more expensive. But a cost analysis conducted by Fakkema for the American Humane Association in 2009 proved that using EBI is actually cheaper.

Another argument is that gas chambers are safer for staff, especially when animals are aggressive. But getting an aggressive animal into an unfamiliar chamber isn’t safe. In fact, chambers can be more dangerous for shelter workers because the gas is so deadly; and in one case, in March 2000, a shelter worker in Tennessee died from inhaling gas while operating a chamber, according to a Chattanooga news outlet.

Training has been—and still can be—one of the biggest barriers to EBI, says Fakkema, who is now retired but spent much of his career providing trainings on EBI. The HSUS has also provided EBI trainings to shelters so they can stop using gas chambers.

Another complication is that controlled-substances laws in some states prevent shelters from getting direct access to the euthanasia drugs for EBI. In these cases, shelters need to go through a local veterinarian. However, The HSUS found there was no correlation between shelters’ use of gas chambers and the state laws regulating access to the euthanasia drugs. While it is obviously preferable if shelters can have direct access, it’s not a prerequisite to eliminating chambers, Fricke says.

Some opponents of EBI say it is too upsetting for staff to have to hold the animal as he dies, says Fricke. “But staff report overwhelmingly that they would much rather see animals go through a very humane transition process than just shove them into a box and walk away.”

Fakkema says in his EBI trainings, shelter staff were sometimes resistant to the new method, until they started doing it.

“They saw that it was easier emotionally on them,” says Fakkema. “It was just simply a far superior method. Oftentimes, what people learn to do with chambers is they learn to load them, to press the button and run. So they didn’t have to hear the animals inside the chamber scratching and whining.”

Compassion fatigue is already a very prevalent issue for shelter workers, and some shelters report that euthanasia can be a main contributor to stress. With that in mind, it’s best that shelters use the most humane euthanasia methods available—for the sake of the animals and the people.

Statewide bans and individual closures

The HSUS made it an organizational priority in 2013 to get rid of gas chambers nationwide and has helped 12 states become chamber-free by securing voluntary closures of individual chambers, helping pass formal statewide bans, or both. Those statewide bans have come in the form of legislation or regulations enforced by an agency that oversees shelter euthanasia.

Some states banned chambers early on—New Jersey was first in 1982, and a smattering of states implemented bans through the ’80s, ’90s and early 2000s, but most of the bans have come in the last decade. Today, 22 states have full, formal bans on gas chambers for euthanizing dogs and cats, while 19 states have no known use of chambers but no formal ban either. Five states have partial bans, prohibiting only carbon monoxide or allowing chamber use under the direction of a veterinarian.

Passing state bans isn’t easy, and even bills with strong public support can get derailed by politics.

That’s what happened in Michigan in 2013, when lawmakers introduced Grant’s Bill (named after a shelter dog killed in a chamber) to make EBI the only acceptable form of euthanasia for cats and dogs. “There was overwhelming public support for the legislation and overwhelming support from the shelters and rescues across the state and from many individual veterinarians,” says former HSUS Michigan senior state director Jill Fritz, now deputy director of wildlife protection for The HSUS.

The bill cleared the Senate but was referred to a committee in the House of Representatives, where it “died a slow death,” says Fritz. One of the committee members was a dairy farmer who made a “slippery slope” argument—first it’s EBI for dogs and cats, and next he’ll have to start euthanizing his dairy cows by injection.

Luckily, The HSUS had a second strategy—engaging local advocates to get individual chambers closed.

The HSUS supports animal lovers who may have no advocacy experience by helping them write testimony and letters to the editor and letting them know what to expect through the process, because testimony is more impactful when it comes from taxpayers and constituents, says Fritz.

HSUS Michigan state council member Virginia Holden lives in Berrien County, which had one of the last chambers in the state, and she was able to convince her county commission to close the chamber. She then used that experience to help local advocates close other chambers that remained in the state.

Holly Thoms, president of the animal rescue and advocacy nonprofit Voiceless-MI, has also been tirelessly working to ban gas chambers in the state, partnering with Holden to achieve voluntary closures and advocating for Grant’s Bill. She says The HSUS helped her know what to expect when talking to state legislators.

Whether you’re at the state or county level, “if you go in there with good intentions and all the facts … you’re going to be in good shape,” Thoms says.

Community impact

Closing chambers also impacts how shelters are seen in the community, and there is no better example of that than North Carolina. Kim Alboum, former HSUS North Carolina state director and current director of the HSUS Emergency Placement Partners program, says the 20-plus chambers there in 2009 plagued the reputations of North Carolina shelters as a whole—even if they didn’t have chambers. When a shelter, which is supposed to be the paragon for humane treatment of animals, doesn’t hold itself to those standards, the community doesn’t want to be a part of it.

Gas chamber closures in the state had to be achieved on a local scale—two separate bills banning gas chambers had been introduced by two animal groups that couldn’t agree on legislative language. The legislature was put off by that, so a state law “was just not going to happen,” says Alboum.

The HSUS offered grants to shelters so they could get rid of their gas chambers and become places where the community wanted to go, says Alboum.

At the same time, she adds, “we wanted to give shelters lifesaving programs” so they could euthanize fewer animals. Grant money went to everything from EBI trainings to expanding cat holding areas to aesthetic improvements.

“A lot of people don’t want to go to a rural shelter—couple that with a gas chamber, forget about it,” says Alboum. “… So when the shelters make this transformation, it really does open it up to the community.”

Vance County experienced this transformation after it got rid of its chamber, with the help of a grant from The HSUS, in November 2012, says Frankie Nobles, chief of animal control. It was a positive change that increased community support for the shelter, he says. It has taken work, though. The stigma of a gas chamber is so damaging that some people still think the shelter uses a chamber, despite public outreach efforts that tried to make it clear that it doesn’t anymore, he says.

Nobles was open to transitioning from the chamber when Alboum approached him because he wanted “to put positive things in our shelter,” he says.

Alboum found that it was important to work with the shelters, asking them how they felt about the chamber, rather than just walking in and “slamming your fist down and demanding change.” Sometimes shelters believe they need more staff to make the switch from chambers to EBI, but often they just need training, she says.

It took support from the public too. At the local level, residents went to county commissioner meetings and wrote letters to the editor. When one shelter closed its chamber, another would feel pressure to do the same. It was almost like a domino effect, so one by one, North Carolina was getting rid of its gas chambers.

(Later, Michigan experienced a similar cascade of closures, when within days of each other in August 2015, the last three counties with functioning chambers decided to eliminate them.)

In North Carolina, by December 2014, there were three chambers left in the state, says Alboum, and The HSUS was gearing up to work on legislation. Then, somewhat surprisingly, the state department of agriculture declared the use of carbon monoxide gas chambers unacceptable as a form of euthanasia for cats and dogs. Though it is a partial ban, it applied to the remaining chambers, making the state gas-chamber-free.

Overall, the experience of closing gas chambers in North Carolina was a “game-changer,” says Alboum, “because it showed the animal advocates that hard work and perseverance and working cohesively equals a win.”

Next steps

In 2017, The HSUS will continue its work to close loopholes in existing bans, pass full chamber bans and achieve voluntary closures of individual chambers. As this issue goes to press, Grant’s Bill in Michigan is awaiting a vote by the end of the 2016 session.

In Wyoming, Bob Fecht, president and CEO of the Cheyenne Animal Shelter, is working with other local groups and The HSUS to close the three remaining chambers in the state, starting by focusing on one shelter. The HSUS has offered it a small grant, and a city council member is assisting the efforts to close the chamber. The shelter seems open to the idea, but it’s not an overnight fix. “People have been doing the same thing for a long time, so it takes time to help change those opinions,” says Fecht.

Ideally, collaboration and shelters helping each other will lead to closures in Wyoming, just like they have in numerous other places, most recently in Coalinga.

The Coalinga shelter still has its issues, but the staff is thankful for the vast improvements the SFSPCA has helped it make. “I hope we have a continued good working relationship ... and can just move forward from here,” says Blevins, of the city police department.

The SFSPCA donated computers and set up a spreadsheet tracking system for recording intakes (shelter software is the ultimate goal, but the shelter is working on getting internet first), and brought in resources—including leashes and hand soap. The SFSPCA helped the shelter get access to euthanasia drugs, but in the meantime transferred animals out of the shelter and sent its own veterinarians to the shelter so animals didn’t have to be put down in the chamber. It also provided EBI trainings for the staff. With this help, plus a grant from The HSUS, the Coalinga shelter is on a better track—and gas-chamber-free.

In July, the governer signed a law to close the California loophole, thanks to work by The HSUS and the SFSPCA.

This kind of collaborative strategy has made gas chambers almost obsolete in the U.S. At the same time, the work to close chambers is a reminder that while the sheltering field has made amazing progress on many fronts, there are still shelters that have been left behind.

To remedy this situation, it can take work like the SFSPCA did in Coalinga.

“It’s just one example of the infinite ways that shelters can lend their expertise and time to other shelters that really need the help,” Kuentzel says. “If every shelter did that … that was in a position to do so, it’s remarkable to think how much progress we can make in animal welfare in the movement as whole.”